|

Excerpts

Darius Milhaud - La Bien-Aimée, op. 101 - Ballet Music with Pianola

and Symphony Orchestra: Rex Lawson

On 22 November 1928, at 9 o'clock in the evening, the Palais Garnier in Paris (the Paris Opera) was filled with an excited and adventurous audience,

waiting to enjoy a whole programme of newly commissioned dance premières, presented by the Russian ballerina, Ida Rubinstein, leading the company that

she had founded seventeen years before. Mme Rubinstein had danced for a while with the Ballets Russes, including appearances as prima ballerina in such

works as Cléopâtre and Rimsky-Korsakov's Schéhérézade.

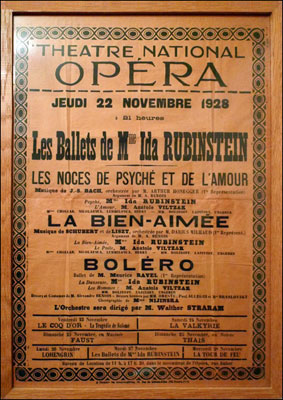

La Bien-Aimée: Poster for the First Performance, Paris Opera, 22 November 1928

The poster for the evening's performance can be seen above, and one can only sympathize with Milhaud that his delightful orchestration shared its

world première with that of Ravel's Boléro! Indeed, it even shared its second performance, in May 1929, with Ravel's La Valse, conducted by the composer

himself, so it is hardly surprising that contemporary reviews gave only a few sentences to Milhaud's work. Let us hope that this article, written eighty-eight

years later (how appropriate for the range of the pianola!), can contribute to the world's appreciation of this long-lost work.

The Russians, the Welte-Mignon and the Duo-Art: Denis Hall

By the time the Duo-Art piano had established itself in America, towards the end of the First World War, many fine pianists had fled Russia, finding life

impossible after the 1917 revolution. We therefore find the names of quite a few Russian-born artists appearing in the catalogue of the American Duo-Art. At

a rough count, 20 such pianists made rolls for that system. With only one or two exceptions, these were of a later generation, and many of them also made fine

disc recordings. The Aeolian Company, manufacturers of the Duo-Art piano, were much more commercially orientated than Welte, and so, regrettably, many

of the titles recorded were of the encore variety, and often of not more than the four minute duration, a restriction of the 78 rpm disc, even though a piano roll

could be made to play for up to fifteen minutes. This is not to say that all Duo-Art rolls are froth; by the demise of the reproducing piano at the end of the

1920s, they had recorded nearly all the Beethoven sonatas, and there are many performances which did not appear in any other format.

Josef Hofmann with a group of his students, including the Russians,

Master Shura Cherkassky and Josef Lhevinne

Top of the list of artists comes Alexander Siloti, a cousin, and for a time, teacher of Rachmaninoff. Siloti was born in 1863, and had a major

career both as a pianist and conductor in Russia before going to the United States in 1922. His reputation never really established itself in the West, and

he lived out the rest of his life teaching and giving the occasional recital. Although he did not die until 1944, he refused to make any commercial disc

recordings. We therefore have to rely on a very few Duo-Art rolls to hear this major Liszt pupil. A fascinating entry in the Duo-Art catalogue lists six rolls

by 'Master Shura Cherkassky, aged 12'. Remarkably, the boy's playing is quite recognisably that of the same mature, adult artist we could hear playing until

the 1980s. Vladimir Horowitz, Nikolai Medtner and Serge Prokofiev all started Josef Hofmann with a group of his students, including the Russians,

Master Shura Cherkassky and Josef Lhevinne their recording careers by cutting rolls, several years before their first discs. Even Stravinsky was enticed into the

Duo-Art studio, although he made a much bigger roll contribution with Pleyel in Paris.

Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915) and his Piano Rolls: Denis Hall

It was in 1910 that Scriabin made his only other recordings, for the Welte-Mignon, when its recording apparatus was taken to Russia. During that

trip, 233 rolls in total were recorded, including some legendary artists such as Konstantin Igumnov, Lev Pouishnov and Alexander Goldenweiser. Sadly,

Welte did not capture the young Rachmaninoff - he was touring in America at that time. Scriabin made six quite short rolls (nine pieces), and these

are full reproducing rolls, which ought to give us the truest representation of his playing. Regrettably, he did not record any major works for Welte.

One wonders if his experience with Hupfeld had made him cautious about attempting anything very ambitious - or was it more a question of his canny

business sense which enabled him to get away with just a few trifles? For whatever reason, these rolls do confirm his reputation as being a master in

interpreting his own works, and are quite remarkable in the freedom and beauty of his playing.

1927 Welte-Mignon catalogue, listing Scriabin's rolls

The only sonic evidence of Scriabin as a pianist, therefore, exists in the fourteen Hupfeld and six Welte-Mignon rolls, a meagre legacy for such a

major figure who lived well into the gramophone era. Of particular value are the Hupfeld rolls of the two sonatas. Even if Scriabin had consented to make

disc records, it is most unlikely that he would have been allowed to record these two major works.

|