This factsheet is currently under construction, but it is hoped that it may be of interest in its incomplete state.

Introduction

It is so very easy for history to become distorted, especially when it only comes down to us by word of mouth. The accepted history of the Welte-Mignon, propagated since the 1950s, would have us believe that

the Welte recording piano registered a separate dynamic level for every single note, and that Welte's editors, whoever they were, converted this note information in some unspecified way into the perforated coding

for two variable suction levels, one for treble and one for bass, which is all that any system of pneumatic reproducing piano is capable of responding to.

In fact, the small amount of documentary evidence that has actually survived contradicts the accepted theory, but it was not discovered, or at least not recognised, until experts of the time had committed their

reputations in the opposing direction. Academic theories of many kinds can take on an almost religious significance, and those interested can find much discussion of Welte-Mignon recording technology on websites

such as the Mechanical Music Digest.

This webpage is an attempt to redress the balance, to sort out what is likely from what is unlikely. Unlike many other pages on this website, it is not intended as a clear and simple explanation for the layman, but

we hope it will prove interesting and thought-provoking.

Richard Strauss recording for the Welte-Mignon - 16 February 1906, Leipzig.

Richard Simonton's Accounts

The previously accepted explanation of Welte recording came down to us mainly through sleeve notes for LPs of Welte-Mignon rolls, all associated with Richard Simonton, an American who became interested in

the subject soon after the Second World War. In the late 1940s, Simonton met and befriended Edwin Welte and Karl Bockisch, who can be seen at the left of the photograph above. Welte and Bockisch, friends from their

schooldays onwards, and at one time brothers-in-law, are generally accepted as the inventors of the Welte-Mignon, though recent researches have suggested that the German-American brothers, William and Henry

Schmoele, may have played an early part in the development of the overall technology.

Over a period of years in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Richard Simonton acquired from the two elderly men many of the rolls which they had kept, either as their personal collections, or from the general

factory library, which was removed well before any danger of war damage was imminent. It is difficult to pin down how much he, himself, knew about the Welte-Mignon recording process, because his earliest LP sleeve notes do not go into great

detail. Those for the subsequent Welte Legacy of Piano Treasures were written by Ben M. Hall, the assistant recording producer, and in private correspondence which survives, Richard Simonton generally avoids giving

detailed information on the subject. There is, however, an audio recording of a Welte presentation at the University of Southern California on 5 January 1964, in which he speaks of his experiences of the Welte-Mignon, and

a transcript of his spoken contribution is reproduced further down this factsheet.

In essence, as the various transcripts demonstrate, Simonton and his collaborators display a number of misunderstandings of the ways in which piano actions and electrical mechanisms operate, and he personally shows a

surprising ignorance of the commercial history of the Welte Company, in both Germany and America, given that he was clearly being treated as the main contemporary expert on the subject. Perhaps he found himself unintentionally

in the spotlight, with musicians and journalists all clamouring for information, and in the end he came up with an explanation that seemed plausible to him, which he thought would satisfy his questioners for once and for

all. Perhaps his main intention was to share with the world the wonders of musical performance that had so captivated him, but the world wanted every last technical detail, which was not really his speciality.

The one basic element which shines through all his confused explanations is the conviction that Welte and Bockisch sought to make their recording mechanism a mirror image of the playback system, a concept that does

not demand a experienced technical mind to understand it. But rather than speculate on Richard Simonton's personal circumstances, it seems sensible to consider the theories that he and his supporters expounded, and to

compare them with what we now know and can logically deduce from all available sources.

Here, to begin, is a transcript of the first post-war description of the Welte-Mignon, reproduced exactly from an early set of Columbia LPs, published around 1950. The author is not credited, but it is clear that Richard Simonton

is being quoted verbatim.

|

|

|

|

COLUMBIA MASTERWORKS LP

Sleeve Note, USA, c. 1950

The story of how these recordings came to be made and of how they achieved permanence on these Columbia discs is a remarkable story which began in the first years of the Twentieth Century

and which involves miracles of engineering skill, patience and wonderful good fortune in the face of what might well have been disaster.

The story, in brief, is this:

At the turn of the century the Welte Company, a German firm already in the forefront of player piano manufacturers, developed and brought to an amazing degree of efficiency a recording device

which could capture on piano rolls the dynamics and phrasing - the personality, in short - of a pianist's performance to a far greater extent than had previously been thought possible. The operation of

this mechanism has been described as follows by Richard C. Simonton, who was largely responsible for securing these recordings for Columbia Masterworks Records.

"There was a standard Steinway grand piano, equipped with a trough running the length of the keyboard and immediately under it," writes Mr. Simonton. "In this trough, there was a pool of

mercury, and when the key was depressed, a carbon rod attached to the bottom of the key engaged this mercury and caused an electrical contact to be made. The resistance of this contact varied

with the pressure exerted on the carbon rod so that actually, depending upon the blow with which the key was struck, there was a corresponding change in the electrical resistance of the contact

made. All of the keys were connected by wires to the recording machine, which was usually some feet away from the controlling piano. This machine had within it the conventional rolls of paper which

were entirely blank and without perforation, but were ruled their entire length with over one hundred fine lines, each corresponding to the center line of its control mechanism. Above the point at which

he impression actually took place on the paper was a series of small rubber rollers of a composition similar to the type used in a printing press, and these rollers were inked with an ink similar to that

used by the printing industry. The result was that as the keys of the piano were depressed, these rollers engaged and transferred their inking to the paper in such a way that, depending upon the blow

or touch exerted upon the keys of the piano, there was a corresponding difference in the inking of the paper on the master roll. Other functions of playing were also transferred, such as pedaling. After

the recording was completed, it was sent to the laboratory and very carefully prepared for being used in the reproducing machine, or used in reverse in order to give a performance and re-create once

again the actual playing of the artist as the roll had recorded it. For this purpose, the Weltes had constructed a machine which was the exact opposite of the recording piano. This device had felt covered

levers - one for each key. It was a cumbersome thing that was placed in front of the keyboard of a piano and when a roll master was put inside, it actuated the mechanism within this monster in such

a way that these levers came down and depressed the keys with the same dynamics in the same order as in the original performance. Every precaution was taken to get conditions as nearly equal as

possible to the original performance, so these wooden fingers were made the same length as a man's fingers from the pivot of his wrist to the tips, so that the same power of touch would produce the

same dynamic strength on the piano as the artist when he struck the keys during the making of the recording."

|

|

Secondly, here is the explanation taken from the Welte Legacy of Piano Treasures, an extended series of LPs published in the early 1960s. This account was written by Ben M. Hall, a journalist working for

the recording producer, Walter Heebner, and the reproducing piano mechanism, which consisted of a Welte Vorsetzer cabinet with a modified Ampico pneumatic stack, was controlled by Kenneth Caswell, who in 2007 is

the sole survivor of the recording staff. It is interesting that Mr Caswell once observed, when recalling a conversation with Ben Hall on the accuracy of his sleeve notes, that the latter had exclaimed, "Well, we

had to sell the records somehow!"

|

|

|

|

WELTE LEGACY OF PIANO TREASURES

Sleeve Note, USA, 1963

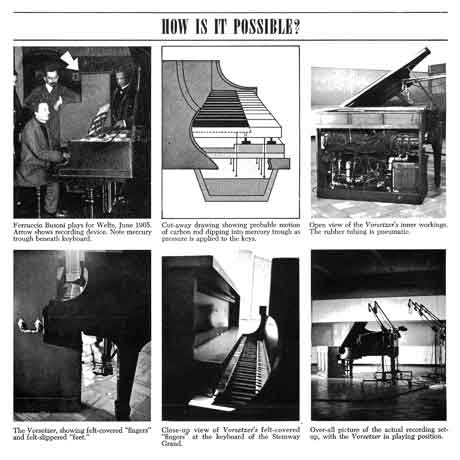

Sleeve Note Illustrations from the Welte Legacy LP Series, USA, 1963.

The most remarkable of all reproducing instruments was a device invented by the German genius, Herr Edwin Welte - circa 1900! Welte, as a matter of fact, invented the first reproducing system

for pianos, a system which was as different from the then-current player piano mechanism (capable only of playing back the notes of the music as perforated on the roll with none of its shading or

expression) as stereo recordings are from Edison cylinders. Edwin Welte gave reproduced piano music a soul.

The Welte recording and reproducing system was a marvel of sheer mechanics. In its way it seems far more remarkable than the electronic wonders of today, and somehow it seems to stand as

a sort of monument to mechanical genius at the peak of its cog-wheeled, cammed and levered, pneumatic glory. It made its debut in 1904; only a few days later, electricity began to take the

spotlight, and the day of the artist-machinist was nearly at an end. Briefly, here is how the Welte worked its magic:

The recording unit, connected to the Steinway in the Musiksaal (music hall), contained a roll of specially aged, thin paper, marked off into 100 parallel lines. Poised over each line was a little wheel

of extremely soft rubber, with pointed edges. Each wheel was in contact with an ink supply, and in this much of the process it resembled a small offset printing press. Under the keyboard of the Steinway

was a trough filled with mercury; attached to the underside of each key was a slim rod of carbon. As the key was depressed, the rod dipped into the mercury and an electrical contact was established

between it and an electromagnet connected to the corresponding inked roller in the recording machine. The harder the pianist hit the key of the piano, the deeper the carbon rod would plunge into the

mercury, and the stronger the current between the rod and thc electromagnet would be. The harder the inked rubber wheel was pressed against the moving paper roll, the wider the mark it printed on

the paper. The pianist's pedaling and speed of attack was captured in the same way.

After a selection had becn finished, the paper roll was removed from the rccording machine and run through a chemical bath to "fix" the colloidal graphite ink which had been printed on it by the

rollers. This ink was electro-conductive, and when the roll was ready to play back, it was put into a master reproducing Vorsetzer which "read" the markings in almost the same way that the magnetic

printing on bank checks is used in automated banking systems today. The Vorsetzer (it means "something set above or before" in German) however, made music as well as money.

Shortly after recording a selection, the artist returned to the Musiksaal and found the Vorsetzer "seated" at the piano where he had been playing. But nobody laughed when the Vorsetzer sat down

at the piano. The results were astonishing. Extending along the front of the cabinet was a row of felt-tipped "fingers" (made the same length as a man's, from the wrist-pivot to the tips, in order to

duplicate human touch), one for each of the piano's 88 notes; two more felt-slippered "feet" stood ready above the pedals. When the machine was turned on, the Vorsetzer re-created the ink markings

into the pianist's own performance, with every pause, every shade of expression, every thundering chord. If the master roll was approved by the artist, it was then laboriously hand punched to translate

the ink markings into perforations in paper rolls which would have the same magical results when played on a standard Vorsetzer in a music lover's home.

Now, in 1963, with one of the few remaining Vorsetzers in the world in place at the keyboard of the nine foot Steinway Grand, with the most perfect studio conditions carefully planned, and with

the priceless treasure of Master rolls to draw from, the WELTE LEGACY OF PIANO TREASURES has been re-created for all posterity.

THE WELTE LEGACY OF PIANO TREASURES has been produced and directed by Walter S. Heebner. Notes by Ben M. Hall

|

|

Thirdly, the following is a transcript of two excerpts from an audio recording made on 5 January 1964 at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, where Richard Simonton was effectively presenting the new series of

LP recordings to the world. This account is much less structured than the written versions, but one should not blame Mr Simonton for any first-night nerves he may have been experiencing. Reproducing piano

recitals can be unpredictable affairs! The presentation was hosted by Professor John Crown, chair of the department of music at USC, and you can listen yourself to the excerpts if you click the appropriate buttons.

|

|

|

|

WELTE REPRODUCING PIANO SYSTEM - Lecture Demonstration Excerpts

University of Southern California, 5 January 1964 |

|

1: Richard Simonton/John Crown - Historical Background

Simonton: Well, the Welte empire, the Welte developments were sort of legends in their own time, and when I was a youngster in Seattle, some of the tales of the musical world up there were of this firm, and what

they had done. I think that Seattle [was important], perhaps more than other sections of the country, because they at one time had had dealers there, who had imported the instruments prior to World War One, so that

there were fairly numerous examples of them in that area. Los Angeles was not so fortunate, and I don't believe other sections of the United States had them to the percentage that we did up

there.

But these people became famous because of their foresight and their vision in their recording technique, not only from the standpoint of creating an instrument capable of capturing this, but in

their vision in employing artists to record, who were to become so famous, largely not only as performers, but as composers as well, and the appeal which the Weltes extended to the artists, or the

appeal that they used to convince them to record for them, was that they were preserving their work for posterity, and no other form was as permanent. Therefore, if the composer wished to be heard

by future generations, then this was the only means available. Therefore, take advantage of it, or else you will be only remembered by the printed page.

So as a result, they were able to convince a number of the famous artists, composers, to record for them, and for a number of years were embarked on quite a campaign of this, traversing the

length and breadth of Europe, even going in to Russia, where they set up temporary recording facilities in St Petersburg, and they recorded there the works of Glazounov and Scriabin, and the famous

Russians of the day, as well as in Paris, where they did Ravel and Debussy, Saint-Saens, Fauré, others equally famous, and then their own main plant in Freiburg, the sort of centre of their

activity, where they ran a regular recording schedule - at least one artist a week, that was brought there for the prime purpose of recording.

This has been a known fact, that they had done all this, but somehow or other it disappeared from view during the days of the Hitler Government, and subsequently through World War Two, but after

the end of the hostilities, it seemed like an intriguing project to try to find out what became of this - where had it gone, had it been destroyed, or did it still exist? So I set out on a campaign

of writing letters, until I eventually found someone that could give me some answers, and it turned out to be Edwin Welte himself. And it was fortunate that they realised that the factory would

probably be bombed, as it was in a prime location, so they had removed these devices, and these master recordings, to a place of hiding in the Black Forest, and after prolonged negotiations, and a

great deal of red tape, not only with our government, but with the French occupying forces, because it was in the French zone of occupied Germany, we finally, my wife and I were finally able to go

over there and bring them back, but only in the form of doing a recording on the spot, with the best that was available at that time, and it certainly wouldn't compare with what's available

today. However, it did whet our appetite for more, and even though we were not able to do it under the controlled conditions that it was later done, we did realise the musical worth of what was

there.

So then in 1952 we went back, and this time the gentlemen had reached an age where their survival would not be many more years - they have all now passed away - and we were able then to bring

back to this country the examples of the machines and the rolls themselves, so that we now have them preserved, and literally everything that exists today, we have here. There's virtually nothing

left.

Crown: Well, by "here", you mean you have.

Simonton: Well, yes, in the United States.

The firm has ceased to exist, largely due to the ravages of war. The firm was founded in 1832, and it existed until, virtually, the Hitler Government put them out of business. It was non-essential

to the German dreams of conquest, so consequently it could be dispensed with, and was, and so they simply - in fact, they had been dispossessed of their building in Freiburg, and it had been

converted to war industries and was therefore a prime target. So literally the only things that could be salvaged were those which they could take out in their hands and put in some place of safe

keeping. I wish that we had been able to, or they had been able to preserve a great deal more, but we're grateful for what they did save.

2: John Crown/Richard Simonton - Technical Explanation

Crown: Now, Dick, I wonder if you would be good enough to explain how the Welte operates?

Simonton: Well, they were very candid in their approach to it, and they realised that the dynamic intensity, or the force with which the key was depressed, the velocity of the key, if that could

be captured, it was the key to the dynamic, the musical nuance. So therefore they evolved a rather elaborate means, and it was electrical, even at a very early day, for recording not only the

sequence of notes, which was not unique in itself, but the dynamic force or the velocity with which the key was depressed. Therefore, by having an accurate record, and a means of re-creating this same

velocity, you would therefore get the same nuances of expression if you could reverse this procedure, and allow it to actuate the piano in exactly the same degrees of force with which the mechanism

that recorded it had been actuated, and this is in effect what they did.

The piano was a standard grand piano, not unique in itself, but beneath the keyboard was a trough of mercury, and attached to each piano key was a carbon rod, and when the artist pressed the

keys, these rods engaged, or dipped into the mercury, and mercury provides a very excellent electrical contact, and so therefore they established not [only] the sequence of the notes, but also the

harder the key was depressed, the further it went into the mercury. It lowered the resistance of the electrical contact. Therefore there was a larger current flow in those which were hit hard, over

those which were hit very softly, and they had a means of recording this with colloidally deposited ink, which was electrically conductive, through a series of little rubber rollers into a recording

machine, and this then captured, on this paper roll, by virtue of the width of the line which it made, whether it was lightly hit, or very heavily hit.

And then they had a reversing process, where they were able to play it back in that form, and the philosophy of the vorsetzer was that by creating the wooden levers which are actuated by the

mechanism, they were actually re-creating the length of a man's finger, from the pivot of his wrist to the average length of his finger, so therefore, by having something which would create the same

amount of force, they could produce, with the same leverage, the same degree, the same relative intensities as the performance which they had captured.

From the original machine, which was entirely electrically operated, operating from the colloidally deposited ink on the roll, they transferred it then, through a translation device, to an

all-pneumatic system, because the colloidal ink was not a permanent form; it was only a reference, from which they evolved the pneumatic system that is used in anything but the initial

recording. The colloidal ink was used only for the initial recording, after which it became a pneumatic record.

And they, I think, were correct in their assumption, that by creating this mechanism, and having it completely reversible, so that it would re-create in exactly the same way with which it was

actuated, they would indeed have a reflection, an accurate reflection of the performance that they were capturing.

|

|

According to Ben Hall's sleeve note, on the Welte Legacy of Piano Treasures LPs, the Welte recording mechanism operated in such a way that, as the pianist played, a small carbon rod attached to the underside

of each key was dipped into a trough of mercury, located under the keybed of the piano, and spanning the whole width of seven octaves. In this way, an electrical contact was made, without greatly affecting the touch of the recording piano, which had to remain sensitive enough for the most fastidious concert pianist. The use of

mercury for switching electricity was an accepted practice of the time, and Charles Stoddard's 1908 patent for the original Ampico recording

piano reveals a remarkably similar design. In fact, the early Ampico system makes use of individual mercury cups for each note, rather than a large bath for the whole keyboard. It would not have been at all easy

to control or regulate sensitive contacts if a single bath had been used. One can certainly see a wooden compartment of some sort under the keyboard in many of the Welte recording photographs, and it is

particularly clear in the case of Ferruccio Busoni's 1907 recording session in Freiburg.

Unlike Duo-Art, Welte did not perforate music rolls in real time, but instead made ink traces on the original roll as the notes were played, and these were subsequently punched out by hand. It is likely that

the paper for these originals was white, and that it was pre-printed with 100 continuous lines, in the positions where each pitch was located. A number of original rolls for the Welte Philharmonic Organ have

survived, and one can see that the positioning of the recorded traces is slightly offset from the pre-printed pitch lines, allowing a roll editor to punch out each note, without destroying all trace of the marked up

performance. Indeed, Welte's processes of recording for the piano and the organ must have been very similar, except for the necessity of recording dynamic information in the case of piano performances.

As we have seen above, the Welte-Mignon dynamic system consisted of slow and fast crescendo and diminuendo mechanisms: slow for overall variation, and fast for accents and sudden changes. The coding for

such a system is at first sight rather simple, but in fact depends heavily on the accurate length and positioning of the relevant perforations. The "Simonton" theory, propounded not so much by him as by his

enthusiastic followers, holds that the beginning of each recorded note trace varied in width according to the speed with which the key was struck. That is to say, it reached its full width at a rate

corresponding to the loudness of the note.

Disregarding the grotesque idea that microscopically thin traces of colloidal graphite ink might conduct enough electricity to operate early twentieth century solenoids, it

is a complete nonsense to suppose that musical editors might somehow read the minutiae of eight-to-the-inch note markings, and translate this into only two sets of generalised coding perforations. Besides, experienced

musicians who listen to Welte rolls on pianos in good condition always remark on the humanity of the performances. A Duo-Art roll can sound magnificent, but one always knows that it is a portrait; all the

dynamic coding is put there for a purpose by a musical editor. In the case of the Welte, there is sometimes a certain coarseness, but equally there are countless tiny little glimpses of reality, moments that no

deliberate attempt to fashion dynamics would have dreamed of.

There is an answer to all this confusion and speculation. Throughout Richard Simonton's explanations of the Welte-Mignon, he constantly came back to the symmetrical nature of the recording and playback

systems. He was absolutely right about this concept, but his lack of expertise in the field of pneumatics caused him to misunderstand the way in which it was achieved. Simonton's working life was with the

Muzak Corporation, at that time purveyors of piped audio recordings for work and leisure; as an audio expert, he looked at the problem of Welte recording, which he didn't really understand in detail, and he came

up with an electronic solution instead of a pneumatic one.

The pneumatic answer is that Welte's recording method can be found in its playback mechanism, not in some notional electrical reproducer, but in the normal Welte-Mignon, with its treble and bass regulators, and its

pneumatic motors and wooden actuators, designed to resemble the length and power of human fingers. One has to remember that in 1904, the Welte Company was already manufacturing electro-pneumatic pipe organs and

orchestrions. Edwin Welte and Karl Bockisch had only to make use of their own workforce and its existing experience.

Suppose a recording device had two pneumatic regulators, one for bass and one for treble, the same size as those in the playback system. Suppose each note had a pneumatic motor associated with it, of the same

size as the playback pneumatics. Suppose that some way could be found of evacuating these pneumatics in a controlled way, depending on the force with which each note was depressed by the pianist. The note

pneumatics might in their turn evacuate one of the pneumatic regulators. Such a system would indeed be the mirror image of the Welte playback. In fact, it would be easy to achieve this pneumatically; all that

would be needed would be some carbon rods, a mercury bath (or a series of them), some small electrical leaf contacts at the rear of the piano action, and two sets of electro- pneumatic valves, devices well known to organ

builders of the time, and identical in reverse to those actually patented by Welte in 1883.

This, then, is how the Welte recording system probably worked. Underneath each key of the piano there was indeed a small carbon rod, which, when the pianist played, dipped into a cup of mercury, one for each

note. As it made contact with the mercury, it operated a small electro-pneumatic valve, causing air to be gradually sucked out of a note-sized pneumatic motor, which consequently began to collapse against a spring. As the leaf

contact at the rear of the piano action closed, a number of milliseconds later, depending on the dynamic force of the note and its associated speed of key depression, it operated a second valve, which connected the note pneumatic to one of the two larger

regulator pneumatics, for bass or treble, depending on the pitch of the note involved. This regulator pneumatic, normally kept evacuated through a controlled bleed hole, would twitch open by means of a spring as soon as any atmospheric air were supplied

to it, and the resulting motion could be used to draw a dynamic line along the side of the recorded roll. Furthermore, by the use of a simple matrix of sprung flap valves and small pneumatics, it would be possible, and indeded simple, to mark the

master roll up with the exact dynamic coding required.

This theory fits with the only documented Welte master roll known to have survived, until it disappeared during the 1980s.

![]()